Client-side encryption for web apps (2/4): Storing the salt and DEK, and encrypting/decrypting data

Fri Jan 17 2025

Discuss this article on Hacker News.

This is a series of articles about client-side encryption. You are currently reading part 2.

Table of contents

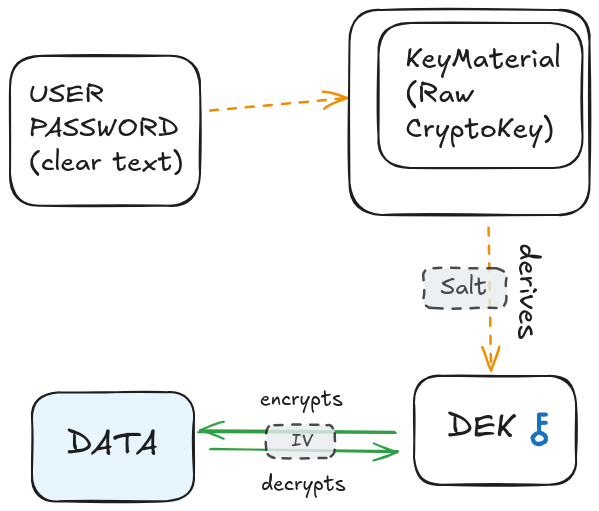

In the last article, we covered the mechanism of key derivation from a password. We also discovered the term DEK (Data Encryption Key). We have generated a DEK and a salt. What’s next?

Storing the salt

We have generated a DEK from the clear-text password of the user (through a key derivation function). We have also generated a salt. This means that if we want to regenerate the exact same DEK we need to store the salt on the backend.

Let’s take a look at our previous users table:

Column ............................... Type

id, autoincrement ................. integer

email ............................. varchar

email_verified_at, nullable ...... datetime

password .......................... varchar

remember_token, nullable .......... varchar

created_at ....................... datetime We need to add a dek_salt column to this table (varchar).

Column ............................... Type

id, autoincrement ................. integer

email ............................. varchar

email_verified_at, nullable ...... datetime

password .......................... varchar

remember_token, nullable .......... varchar

dek_salt .......................... varchar

created_at ....................... datetime When a user registers, our client-side app generates both a DEK and a salt. We then send the email and password as well as the dek_salt (a base64 string) to the backend. Providing a dek_salt at registration is now mandatory: omitting it will trigger a validation error.

When the user logs in later, we keep the clear-text password of the user in memory for a very short time (in our JS framework), and we use the salt returned by the backend (on authentication success) to generate the DEK again. We transform the base64 salt into a Uint8Array and use it to generate the DEK back.

// on login success

const saltString: Base64String = response.data.dek_salt;

const salt: Uint8Array = base64ToUint8Array(saltString);

const dek: CryptoKey = await generateDek(

userPassword,

salt

);What about the DEK?

The DEK we have is a CryptoKey object. It can be stored in memory, if you have a Single-Page Application. The question is: what happens if the user refreshes the page or closes the tab? We then lose the DEK. We don’t have any way (for now) to avoid sending the user to the login page again. Let’s see how to fix this. This will be useful for page refreshes, but also if the user wants to stay connected to the site with a “Remember me” option.

Storing the DEK

Since the backend must know nothing from the DEK, using cookies is not an option. The obvious idea coming to mind is to use localStorage or sessionStorage. This is quite simple.

It would probably be more secure to use sessionStorage (since the data is deleted when the tab is closed) but we want to keep the DEK even if the user closes the tab (our user will use a _remember me_token). We will then use localStorage.

Obviously, when a user logs out, it’s important to delete all the user’s data from localStorage.

Since localStorage can only store strings, we have to convert the CryptoKey object to a string. We first have to export it to a raw Uint8Array, then convert it to a base64 string. We already have our function to convert a Uint8Array to base64.

Unfortunately the exportKey method doesn’t return a Uint8Array, but an ArrayBuffer. We can easily convert it to a Uint8Array though.

To be honest, I still have trouble understanding the exact relation between Uint8Array and ArrayBuffer. I guess we don’t need to dive into this for what we’re doing here. You can read about ArrayBuffer here.

async function cryptoKeyToBase64(key: CryptoKey): Promise<Base64String> {

const rawKey: ArrayBuffer = await crypto.subtle.exportKey('raw', key);

return uint8ArrayToBase64(new Uint8Array(rawKey));

}This simple function gives us a base64 string from a CryptoKey object. We can now store it in localStorage very easily:

// 'WGObg9QpgtfaJ3Dk9hg1x2tnHq/kKQnLfUxvW7SS5vA='

const dekBase64: Base64String = await cryptoKeyToBase64(dek);

localStorage.setItem('dek', dekBase64);Every time we generate the DEK, we keep the CryptoKey object in memory in our JS framework, and we also store its base64 representation in localStorage. This way, if the user refreshes the page, we retrieve the string representation of the DEK from localStorage and import it back as a CryptoKey object.

We will create a function to create a CryptoKey object from a Uint8Array and another being just a simple wrapper to convert a base64 string to a CryptoKey object. It gives us more flexibility and we could need it later.

async function uint8ArrayToCryptoKey(

keyString: Uint8Array,

exportable: boolean = true,

): Promise<CryptoKey> {

return await crypto.subtle.importKey(

'raw',

keyString,

{ name: 'AES-GCM' },

// We make this a parameter of our function because

// it will be useful later

exportable,

['encrypt', 'decrypt'],

);

}

async function base64ToCryptoKey(

keyString: Base64String,

exportable: boolean = true,

): Promise<CryptoKey> {

const raw: Uint8Array = base64ToUint8Array(keyString);

return await uint8ArrayToCryptoKey(raw, exportable);

}Then, to generate the CryptoKey object from the base64 string we stored in localStorage:

const dekBase64: Base64String = localStorage.getItem('dek');

if (dekBase64) {

const dek: CryptoKey = await base64ToCryptoKey(dekBase64);

} else {

// We logout the user and redirect them to the login page

}exportKey also allows to export keys in the JWK format. This format is a JSON object dedicated to storing cryptographic keys. It is a standard format, especially useful to store a pair of public and private keys. You can read more about JWK here.

In our case, we only have a simple symmetric key, so I don’t think it adds any value to use JWK compared to base64 (please correct me if I’m wrong).

We will see later if there is a better way to store the DEK. For now, serializing it to base64 and storing it in localStorage does the job.

Encrypting and Decrypting Data

We can finally encrypt and decrypt data. Instead of storing the amount value as an integer in our database we will now store an encrypted_amount as a string.

The consumptions table as we described it before:

Column ............................... Type

id, autoincrement ................. integer

user_id ........................... integer

day .................................. date

amount ............................ integer

Foreign Key .......................

user_id references id on users ....Now:

Column ............................... Type

id, autoincrement ................. integer

user_id ........................... integer

day .................................. date

encrypted_amount .................. varchar

Foreign Key .......................

user_id references id on users ....I first thought it would be a problem to encrypt the amount alone as it would result in the same encrypted data for the same input value. Even if we can’t decrypt the value itself, seeing that every Saturday there is the same encrypted value that is different from the ones seen on other days during the week could give some information about the drinking habits of the users. It would be easy to deduce that the user drinks the same amount every Saturday (and if the data is not the one seen during the week, we could probably infer that our user drinks more on weekends).

So my first thought was that instead of encrypting the amount alone we could encrypt an object containing the amount and the day. Something like this:

// Even if the amount is the same

// the encrypted data changes every day

const data = {

amount: 3,

day: '2025-01-09',

};

async function encryptData(

key: CryptoKey,

data: Object

): Promise<Base64String> {

// ...

}This was before I knew how the crypto API works. When we encrypt and decrypt data with AES-GCM, we must provide an IV (Initialization Vector).

Think of an IV as similar to a salt but used for encryption/decryption. A salt makes it possible that the same password gives a different hash. An IV has the same role when it comes to encrypted data. The same input data will give a different encrypted data if the IV is different. You then need to give the same IV to decrypt the data.

We therefore need to generate a new random IV every time we encrypt data, and store it alongside the encrypted data. We will store the IV as a base64 string.

Since we will use a random IV every time we encrypt amount, the output will always be different and won’t give us hints about the input.

Let’s add the IV to our consumptions table:

Column ............................... Type

id, autoincrement ................. integer

user_id ........................... integer

day .................................. date

encrypted_amount .................. varchar

iv ................................ varchar

Foreign Key .......................

user_id references id on users ....We first create a function to generate our IV:

function generateIv(): Uint8Array {

// This is 12 bytes long (96 bits)

return generateRandomKey(12);

}We follow the recommendation found in the MDN docs:

The AES-GCM specification recommends that the IV should be 96 bits long.

Note that the IV does not have to be secret, just unique: so it is OK, for example, to transmit it in the clear alongside the encrypted message.

We can then encrypt data:

type EncryptionResult = {

iv: Base64String;

encryptedData: Base64String;

};

async function encryptData(

key: CryptoKey,

data: any,

): Promise<EncryptionResult> {

// Everytime we encrypt something we

// use a new random IV

const iv: Uint8Array = generateIv();

// In our case, the data is an integer but we make this

// implementation generic so that we can encrypt anything

const serializedData = JSON.stringify(data);

const encryptedData: ArrayBuffer = await crypto.subtle.encrypt(

{ name: 'AES-GCM', iv },

key,

new TextEncoder().encode(serializedData),

);

return {

// We return the iv as base64 string

iv: uint8ArrayToBase64(iv),

// We return the encryptedData as base64 string

encryptedData: uint8ArrayToBase64(new Uint8Array(encryptedData)),

};

}And we can store the iv and the encryptedData in the database.

/*

{

iv: "+c1Ubll95bP0Vk7S",

encryptedData: "h/LAb9bgsfPVuWm0NlIgMp8="

}

*/

const { iv, encryptedData } = await encryptData(dek, 3);I’ve noticed after some tests that with a 12 bytes-long IV and an amount between 0 and 5, the encrypted amount (once serialized as base64) is always 24 characters long.

And the IV is always 16 characters long (serialized).

So on the backend, I validate the encrypted_amount and the iv to make sure they have this exact length.

Since data is encrypted I cannot validate the input on the server. This means if I store encrypted_amount as a longtext, some smart users could use my app as some storage for files or something else. Always restrict the length of the encrypted data.

Users will be able to bypass client-side validation and break their app (hey, it’s their choice) but they won’t be able to store crazy things.

When the user goes to a new page, we retrieve the iv and the encryptedData from the backend and we decrypt data to show it to the user:

async function decryptData(

key: CryptoKey,

iv: Base64String,

encryptedData: Base64String,

): Promise<any> {

const decryptedData: ArrayBuffer = await crypto.subtle.decrypt(

{ name: 'AES-GCM', iv: base64ToUint8Array(iv) },

key,

base64ToUint8Array(encryptedData),

);

const decoded: string = new TextDecoder().decode(decryptedData);

return JSON.parse(decoded);

}

// 3

const decryptedData = await decryptData(dek, iv, encryptedData);Success! We now have a functional implementation of client-side encryption.

If you’re curious about performance, I checked the time it takes to encrypt and decrypt data. On my computer, encrypting an amount takes 0.06ms on average. Decrypting it is even faster: 0.03ms on average.

Here you can find a gist of the code we have implemented so far.

While our current implementation works, it still has flaws. In the next article we will learn about KEK (Key Encryption Key) and how it could improve our workflow.

Discuss this article on Hacker News.