Client-side encryption for web apps (1/4): PBKDF2, DEK and CryptoJS

Thu Jan 16 2025

Discuss this article on Hacker News.

This is a series of articles about client-side encryption. You are reading part 1.

Disclaimer: I’m not a security expert, so take everything I say with a grain of salt (sorry for the pun). Ask for advice from a security expert if you plan to implement this in a production environment.

Table of contents

Update (22/01/2025): The original title of this series was “E2EE for Web Apps” (E2EE meaning end-to-end encryption). I realized my implementation is not E2EE but client-side encryption. I updated all the series to fix this mistake and talk about the differences.

The story began when a few friends and I realized there was no good and simple web app to track alcohol consumption. We had a few simple requirements and I thought it would be super easy to code. Fair enough. This would be for my friends and myself, but I also planned to make it public for anyone interested in tracking their health habits.

At some point, I discussed this project with a friend who is also a dev (check his cool blog btw). He answered with a question: "Isn’t storing alcohol consumption linked to an email in clear text a problem? ". Sensible question. What if my app gets breached, and someone has access to my db containing the alcohol consumption of users?

The goal of this series of articles is to document my findings (step by step) about client-side encryption and also to get some feedback about my approach. If you think anything is weird or wrong, please tell me! I’m here to learn. You can ping me on Twitter, Mastodon or BlueSky.

This series will be updated if I receive relevant feedback.

First thoughts and requirements

A way to get rid of this problem would have been not to store anything sensitive (alcohol consumption) in the db, but to rather store this in a secured cookie in the browser. This solves the problem of privacy but it would have meant people would lose their data whenever they switch to a new device or browser. Given that I expect this kind of app to be used in the long term (one year or more) this was out of the question for me.

I also wanted this to be a web app and not a native app: people should be able to browse the app from their phone (iOS or Android) but also from their computer.

This leads to the following question: could I imagine a web app, where the server has no access to sensitive data?

This is how I dove for the first time into things like PBKDF2, AES-CGM, or cryptoJS.

Let’s go!

The journey begins

The app has very few and simple features:

- A user registers/logs into the app.

- A user can select a day in the current (or past) month and choose a level of alcohol consumption. This is a just an integer, from 0 to 5, where 0 means “None” and 5 means “Wasted”.

- In the month view, each day is represented with a different color according to the amount chosen for this day.

- There is also a year view where we show the same data but for a whole year.

- A user will never share their content or see the content of another user.

Let’s start by looking at the db schema an app without encryption could use:

users:

Column ............................... Type

id, autoincrement ................. integer

email ............................. varchar

email_verified_at, nullable ...... datetime

password .......................... varchar

remember_token, nullable .......... varchar

created_at ....................... datetime consumptions:

Column ............................... Type

id, autoincrement ................. integer

user_id ........................... integer

day .................................. date

amount ............................ integer

Foreign Key .......................

user_id references id on users ....We won’t mention here which backend framework I use because it’s irrelevant.

My goal here would be to get an encrypted amount value and not being able to know what’s in there.

Choosing the right threat model

One of the most commonly advised first steps when talking about security is to think about the threat model. Who is your adversary and what are the strategies you could implement against them?

- The first person I want to prevent from accessing data is myself: we all have heard stories about an employee making a mistake, publishing things they didn’t intend to, or (more commonly) storing sensitive information in the logs.

- The second potential threat is a hacker who could get into my server and steal the database.

The advantage of this small project is that although this data is quite sensitive (your alcohol consumption and unhealthy habits are no one’s business) it’s not as sensitive as banking information. This allows me to think of a good encryption model but if it contains a bug it would not be as dramatic as other applications.

One of the first ideas that came to mind was: "can’t I encrypt the amount on the backend when fetching or updating the database? ". Indeed, most web frameworks these days provide a way to encrypt/decrypt a value based on a key. We could imagine encrypting each user’s data with a key we have generated for them and stored at signup. This would not help in our case:

- An attacker having access to our server could get this key.

- We would still handle the data in cleartext on the server which would allow the developer to make mistakes.

I needed a more complex solution and wanted to see how far I could go: could I build something where, as a server, I have absolutely no clue about the amount stored by the client in my db?

I then started to look for answers about client-side encryption.

A weird lack of resources

As developers, we hear more and more about encryption these days:

- "Are direct messages on Twitter encrypted? " (no, I won’t call it X, sue me)

- "Sure, WhatsApp is supposed to use E2EE for their messages, but do they encrypt metadata? "

- "You should use Signal, it’s using proper E2EE "

Although we feel like it’s an important topic and more apps should use it, I was surprised to find so few articles and resources about it. Most of the resources I found were questions and answers on Security StackExchange.

Also, most of them were written in the context of a messaging app. Since it is the most discussed use case, it’s not that surprising. In this context, the idea is to generate a pair of public and private keys for each user, so that they can exchange messages without the server knowing what they’re talking about. I won’t dive into this kind of model because my use case is different: my users won’t communicate between each other and nothing from a different user will be visible, so having a pair of public/private keys is probably not adapted to my app.

Update (22/01/2025): This lack of resources found is probably partly related to my initial mistake. I thought my implementation was about E2EE (end-to-end encryption) but it’s actually client-side encryption.

Here are the main differences:

- End-to-end encryption (E2EE) means two people communicate through a server in the middle. The server knows nothing about the content that is sent by both parties. Alice and Bob can communicate together and the server hosting the messages cannot decrypt them.

- Client-side encryption means Alice can store things (for herself) on the server, and the server cannot read her data.

- E2EE involves asymmetric encryption (public/private keys)

- Client-side encryption involves symmetric encryption (one key for encryption and decryption)

Some services use both. Client-side encryption is used to store data on the server and E2EE is used to share data between users.

This series was initially supposedly about E2EE but it was a misconception of mine. We talk here about client-side encryption (symmetric encryption). We might dive in a future series into E2EE.

I only need one key for each user that will be used to encrypt/decrypt the data sent to and received from the server.

When it comes to this kind of encryption setup, I have to say resources are scarce and I had to rely on LLMs and personal experiments.

This is why I’m writing this article: I hope it will help someone in the future but I also want to get feedback on my approach and see if I’m doing something wrong.

First approach

A few years ago, I read a blog post from the Proton team about zero-access encryption and how they proceed to avoid having access to their users’ data. I kept in mind they had a key for each user generated from their password in clear text, directly in the browser. This key was then used to encrypt/decrypt the data client-side.

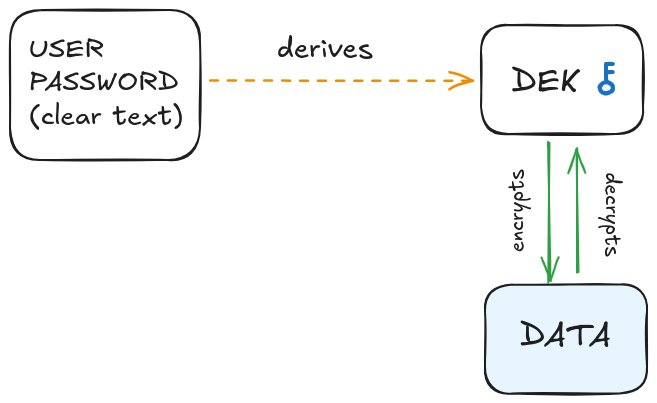

Fair enough: my goal is to encrypt the amount value in the browser before sending it to the server, thanks to a key generated from the user’s password. This key will be generated on registration (and generated again on login). I have read a few things about this process and this is where I started reading the word DEK.

A DEK is a Data Encryption Key. It’s a key that will be used to encrypt/decrypt the data from the user. From now on, I will use this term to refer to the key used to encrypt and decrypt user data.

A few questions already:

- How do I generate a DEK from a password?

- Should I store the DEK client-side somewhere?

- How do I encrypt/decrypt data with this DEK?

- Which algorithm should I use?

Let’s try to get something basic working and we will then iterate on it.

Generating a key from a password

We first want to know how to generate a key from a password (basically, clear text), directly in the browser.

There is a well known algorithm for this: PBKDF2. It stands for Password-Based Key Derivation Function 2. PBKDF2 is the proud successor of… PBKDF1 (you guessed it) and it can produce a cryptographic key from a password. The official term for this operation is derive. So we will derive a key from the user’s password.

PBKDF2 is known to be a slow key derivation algorithm, which prevents brute force attacks. It takes a password, a salt, a number of iterations, a hash function (we will talk about this very soon), and a key length.

At this point, you’re maybe thinking (like me): "What you’re describing looks exactly like a password hashing algorithm ". And you’d be quite right!

There are differences though: a key derivation function’s purpose is not to create a password hash but to create a key that will be used for encryption. Notice that we have to specify the length of the key we want to generate. Some hashing algorithms (like bcrypt) will generate a hash of a fixed length. This means we can’t use bcrypt to generate a key of 256 bits.

On the other hand, you can use PBKDF2 (as long as you use the right hash function and the right parameters) to hash a password.

You can read more about why bcrypt is not a KDF (Key Derivation Function) here.

PBKDF2 requires a hash function: typically one of several SHA versions. Basically, SHA by itself cannot be used to safely generate a key or a hash (because it’s too fast and doesn’t handle iterations and salt), but PKBDF2 will use it to generate a key. This is how the Django framework hashes passwords by default (PBKDF2+SHA-256). We will also use SHA-256 here, to generate our key.

We also need to know the algorithm that we will use to encrypt/decrypt the data. We will use AES-GCM (Advanced Encryption Standard - Galois/Counter Mode). This is a symmetric encryption algorithm, which means the same key will be used to encrypt and decrypt the data. We need to know this before generating the key because we need to specify the algorithm which will use this key later.

As we will see in a later article, AES-GCM is quite fast to encrypt/decrypt data. It’s quite good for our use case because in my year view, I need to potentially show 365 days of data (which means 365 encrypted values to decrypt on the same page).

Okay! I think we have everything we need to show some JS code. JavaScript has a built-in crypto built-in JS library which is available in the browser, to handle all this encryption stuff.

Let’s start by showing some pseudo code of how I imagine things, and we will replace each part progressively to understand what’s happening.

// Here we hardcode a password for the example

// but we obviously take the one the user has entered

// in the registration form

const userPassword = '...';

function generateSalt() {

// ...

}

const salt = generateSalt();

async function generateKey(password, salt) {

// ...

}

const dek = await generateKey(password, salt);From now on, the code shown will be in TypeScript. I think it’s easier to understand what’s happening.

To generate the salt, we can use the crypto library, which has a method called getRandomValues. It generates a cryptographically strong random value.

One important thing to notice is that it will not return a string but a Uint8Array. This is a typed array that represents an array of 8-bit unsigned integers.

This is what all crypto operations will use: Uint8Array. We have to keep this in mind when dealing with this type of data. If we want to store it in a database or in the localStorage, we will have to convert it to a string (base64 for example).

Don’t be scared by this new type: Uint8Array. You can learn more about it here.

It represents raw binary data. In Python you would use the bytes type instead.

function generateRandomKey(length: number): Uint8Array {

// This will return a secure random Uint8Array of `length` bytes

return crypto.getRandomValues(new Uint8Array(length));

}

function generateSalt(): Uint8Array {

return generateRandomKey(16);

}We can already add functions to transform a Uint8Array to a string (base64) and vice-versa because it will become handy later (don’t worry if these look complicated. You don’t need to understand the detail of their implementation).

type Base64String = string;

function uint8ArrayToBase64(bytes: Uint8Array): Base64String {

return btoa(String.fromCharCode(...bytes));

}

function base64ToUint8Array(base64: Base64String): Uint8Array {

const binary = atob(base64);

const bytes = new Uint8Array(binary.length);

for (let i = 0; i < binary.length; i++) {

bytes[i] = binary.charCodeAt(i);

}

return bytes;

}We have our salt ready, and I thought we would then pass our clear-text password directly to a crypto method to generate the key.

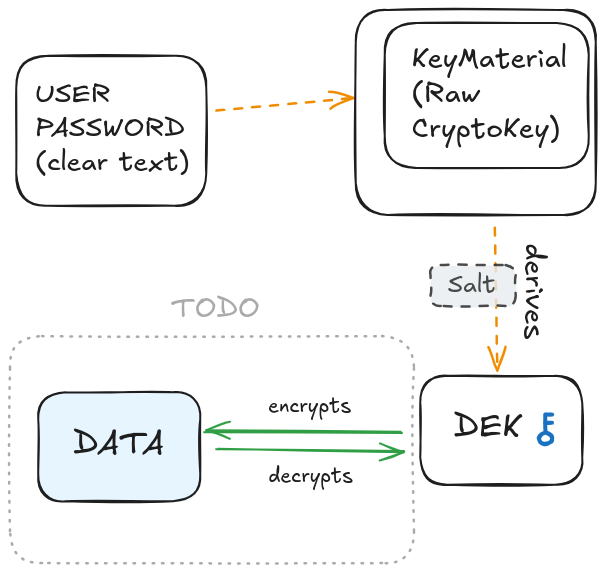

We actually need an intermediate step. In order to generate a key from a password, crypto needs to wrap the password into a special object.

To do this, we will use crypto.subtle.importKey. This method will take the password as a Uint8Array and will wrap it into a CryptoKey object.

const salt: Uint8Array = generateSalt();

const keyMaterial: CryptoKey = await crypto.subtle.importKey(

'raw',

new TextEncoder().encode(userPassword),

{ name: 'PBKDF2' },

false,

['deriveKey'],

);Let’s break this down:

const salt: Uint8Array = generateSalt();

const keyMaterial: CryptoKey = await crypto.subtle.importKey(

// We specify the format of the key we want to import

// Here nothing special, it's a raw key (our clear-text password)

'raw',

// The source value of the key

// Here we transform the password (a string) into a Uint8Array

new TextEncoder().encode(userPassword),

// We specify the algorithm we will use

// to derive the key later

{ name: 'PBKDF2' },

// We specify if the key is extractable

// Extractable means that you can extract the

// value itself from the key object later

false,

/*

* We specify the operations we want to allow

* on this key later

*

* Other possible values here:

* [

* 'encrypt',

* 'decrypt',

* 'sign',

* 'verify',

* 'deriveBits',

* 'wrapKey',

* 'unwrapKey'

* ]

*/

['deriveKey'],

);You can read more about the importKey method here.

I was a bit surprised we have to specify the algorithm we will use to derive the key here. At this point it doesn’t do anything, but crypto requires it. If the key has been imported for a different algorithm, it will not allow the operation.

Once we have the keyMaterial, we can use it to derive a key. This is where we will finally use PBKDF2.

async function generateDek(

keyMaterial: CryptoKey,

salt: Uint8Array

): Promise<CryptoKey> {

return await crypto.subtle.deriveKey(

{

// We use PBKDF2 to derive the key

name: 'PBKDF2',

salt: salt,

iterations: 600_000,

hash: 'SHA-256'

},

// Our crypto key material

keyMaterial,

{

// The algorithm we will use later

// to encrypt/decrypt the data with this key

name: 'AES-GCM',

// The desired length of the key

length: 256

},

// Yes, we want to be able to extract

// it later (as Uint8Array)

true,

// The operations we want to allow on this key

['encrypt', 'decrypt'],

);

}We use 600 000 iterations to follow the OWASP recommendations.

We now have our DEK! We can use it to encrypt and decrypt data.

Let’s refactor things a bit and recap the code we have so far:

function uint8ArrayToBase64(bytes: Uint8Array): Base64String {

return btoa(String.fromCharCode(...bytes));

}

function base64ToUint8Array(base64: Base64String): Uint8Array {

const binary = atob(base64);

const bytes = new Uint8Array(binary.length);

for (let i = 0; i < binary.length; i++) {

bytes[i] = binary.charCodeAt(i);

}

return bytes;

}

function generateRandomKey(length: number): Uint8Array {

// This will return a secure random Uint8Array of `length` bytes

return crypto.getRandomValues(new Uint8Array(length));

}

function generateSalt(): Uint8Array {

return generateRandomKey(16);

}

async function generateDek(

password: string,

salt: Uint8Array,

): Promise<CryptoKey> {

const keyMaterial: CryptoKey = await crypto.subtle.importKey(

'raw',

new TextEncoder().encode(password),

{ name: 'PBKDF2' },

false,

['deriveKey'],

);

const dek: CryptoKey = await crypto.subtle.deriveKey(

{

name: 'PBKDF2',

salt: salt,

iterations: 600_000,

hash: 'SHA-256',

},

keyMaterial,

{ name: 'AES-GCM', length: 256 },

true,

['encrypt', 'decrypt'],

);

return dek;

}

const userPassword: string = '...';

const salt: Uint8Array = generateSalt();

const dek: CryptoKey = await generateDek(userPassword, salt);

// 'bduYb/cMqAXwd3muWT4lng=='

const saltString: Base64String = uint8ArrayToBase64(salt);We now have a DEK (as a crypto key object) and a salt encoded in base64.

In the following article, before diving into the encryption/decryption details, we will talk about what to store on the backend and the frontend.

Discuss this article on Hacker News.